Written by: Mac Potter, Sales Key Account Manager, 4iiii Innovations Inc.

It was 4:50 am and I woke up to what sounded like a car alarm going off outside of my house. In a tired daze I came to realize that it’s just my phone alarm. I wiped the sleep from my eyes and I got out of bed, it was time to ride. Before setting off I slammed a cold brew coffee (that had been in my fridge since last summer’s Sea Otter Canada) and three stale pancakes made the day before which I drenched in maple syrup, magically bringing them back to life. After a quick breakfast, kit on, and power meter calibrated, I headed out the door for what was to be an epic day on the road.

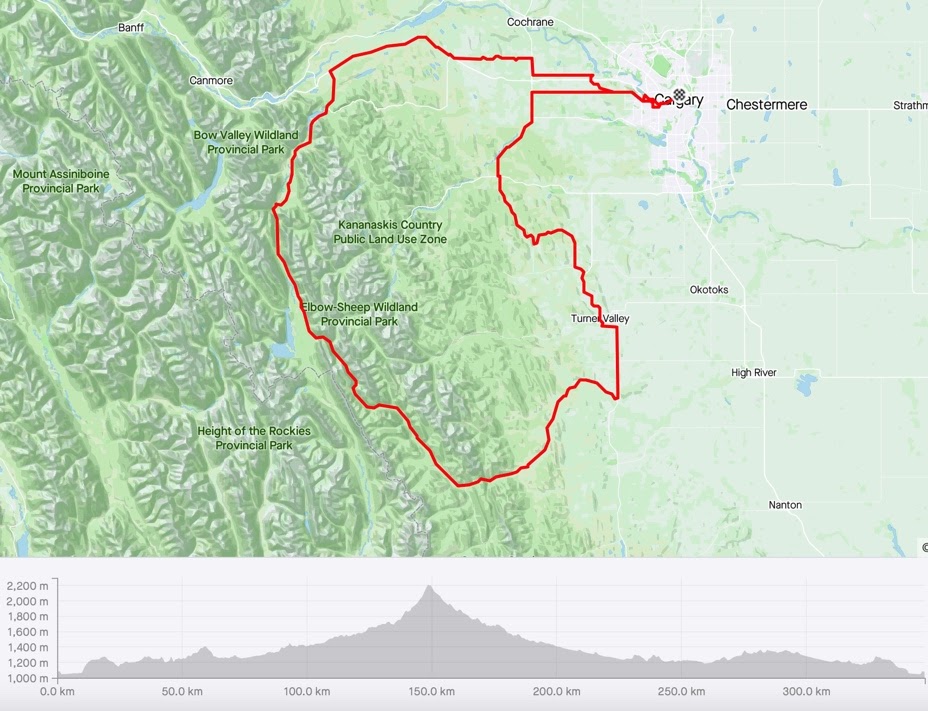

I was not setting out on this adventure alone, and admittedly this ride was not even my idea. Due to Covid-19, races across North America were cancelled. My co-worker Bailey, who is 4iiii’s Sales Account Manager for America, thought of this crazy idea – what if we trained to do Highwood Pass door to door in one single ride? Highwood Pass (located in Kananaskis Country, Alberta, Canada) is a cyclists paradise. Up until June 15th the road is completely closed to all traffic, allowing cyclists to have the mountain pass all to themselves. It’s a once a year opportunity to enjoy the beautiful vistas of the Rocky Mountains worry free. What makes this pass significant is that it’s also the highest paved road in Canada, topping out at 2206m. Once the snow melts in late May, you will find your Strava feed inundated with Highwood Pass rides. It has become an annual tradition with most cyclists in Southern Alberta, Canada to complete before that June 15th date. Most riders choose to do this ride as an out and back making the typical route 110km, but starting and ending in Calgary was going to turn it into a 347km mission.

By 6:00am the four of us, Bailey, Mike, Scott and myself, were together and we officially started our ride. As we knew that we were in for a long day, we set one ground rule at the start of the ride. Pulls were to be kept at 250w and around the 5 minute mark. Mike commented that holding 250w was going to be hard…because it’s tough to go that easy. Mike, who is 4iiii’s Director of Engineering, has been using Trainer Road to train religiously in 2020. Since January, he’s raised his Threshold from 290w all the way up to 333w, or roughly 4.8 w/kg. Riding with Mike is like riding with a kid on a sugar high who just finished a package of Fun Dip, but the sugar high lasts the whole ride and seems to peak on any presence of an incline. Admittedly, the 250w pull rule was more for Mike then the rest of the team that day. Heading out of Calgary Mike took to the front, riding tall and relaxed on his hoods leading us up the first kicker. At 250w, I let Mike know that he passed his first test and we were off, getting us that much closer to the mountains.

After about an hour and a half of riding a low flying owl swooped across the quiet road while we approached our first challenge of the day. “A good omen!” Mike commented as the owl flew off into the distance while hunting for a field mouse with the same determination as Bailey looking for an expired Clif Bar in his back jersey pocket. Bailey, who manages our North and South American sales channels, was adamant that we added a 7km gravel portion to our ride even though we were all rolling on 25c road bikes. My guess is that for 7km he wanted to relive his glory days as a pro cyclist and bring back the now distant memories of racing in the Tour of Alberta. Although Bailey has pro pedigree in his blood from 5 years of racing the North American continental circuit for Red Truck and H&R Block, he was the one that we were most worried about on this adventure. Bailey’s training for this event consisted of 1 hour mountain bike rides followed by beer and hot dogs in the parking lot, randomly selected 45 min Trainer Road workouts that looked “fun”, adjusted to what he felt his FTP was that day, and a few “repeats” on a 1km climb around the corner from his house. Although Bailey didn’t put in the training hours for this “mission” that he created, he will unapologetically remind you that he can still hold 1000w for 20 sec and close to 500w for 2 minutes…even if he can only do it once. Bailey is a soul rider now, but you can always pull the inner racer out of him with a few pokes.

Scott and Bailey fueling up before hitting the Unofficial Strade Bianchi Alberta 7km Group Ride Championship portion of our ride

Scott and Bailey fueling up before hitting the Unofficial Strade Bianchi Alberta 7km Group Ride Championship portion of our rideAs Bailey and I flew through the gravel section, Scott and Mike were closely behind but riding a bit more cautiously, clearly on less of a suicide mission then Bailey who was busy leading the charge through the loose and washboarded gravel road. We finished the sector with no flats, no crashes, and Bailey was crowned the unofficial Strade Bianchi Alberta 7km Group Ride Champion. We took a quick pit stop to chow down a few Snickers bars and turned onto the Trans Canada Highway. For those not familiar, the Trans Canada Highway connects Canada from Coast to Coast and is the main corridor for anyone travelling across the country. We decided to up the pulls to 300w to get through this 25km section quickly as even at 8 am, it was still quite busy with adventurers on their way to the mountains and semi drivers blasting their way to Vancouver, British Columbia. Having ridden from Vancouver to Calgary a few years prior I was unphased by the passing semis, but Bailey was eager to push the pace as apparently riding the Trans Canada was his worst nightmare come true.

After covering 25km in only 40 minutes, we turned south and started heading into the Rocky Mountains. With the crisp mountain air and the sun radiating on our backs, we took our first pitstop at the Centex just across from the forever “reopening” Fortress ski resort junction, which has seen more movie sets than skiers in the past decade. We refilled our bottles with Gatorade and kept heading Southwest towards the base of the climb. We met my girlfriend Jaylene at the base of highwood pass who parked in the shoulder and turned her Tacoma into a fully stocked aid station. With a few mini cokes, fresh pizza buns, and a handful of potato chips we made our way to the gate. Sticking with our rule of 250w we paced the climb at a steady tempo. Starting at 1690m my heart rate was steady in the high 130’s. The effort felt manageable, but the altitude immediately took effect at the 2000m mark. Our mountain bike trails frequently touch the 1900m mark so for myself, edging above this point was an altitude that my body was far less accustomed to. It was obvious from looking at the data being broadcasted from my Viiiiva that the wheels were starting to fall off. The last 200m of climbing my heart rate climbed from 143 BPM to 160 BPM (max is around 176 BPM) all while steadily holding 250w. Mike even half jokingly asked Bailey, who formerly held the KOM on this climb, if we were at the top yet, unfortunately we were not.

Scott chose to still ride in the shoulder even on the closed road while Mike sets the tempo up Highwood Pass.

Scott chose to still ride in the shoulder even on the closed road while Mike sets the tempo up Highwood Pass.Cresting the top at 2,206m, we caught our breath and began the 37km 700m descent. We had a bit of a headwind on the way down so we stuck to our 250w pulls to keep the speed high on the way down. As it was the final weekend to ride Highwood car free, the descent was as busy as commuting along an urban bike path. We were consistently yo-yoing a group of cyclists who would push the little kickers while we stayed steady for the entire descent. Our groups joined, and by the end of the descent we had amassed a peloton of around 30 riders which was pushing the pace as if the south gate were the finish line in a Tour de France stage. Like playing tactics in a road race, we stayed at the back and enjoyed the free ride for the last few kilometers.

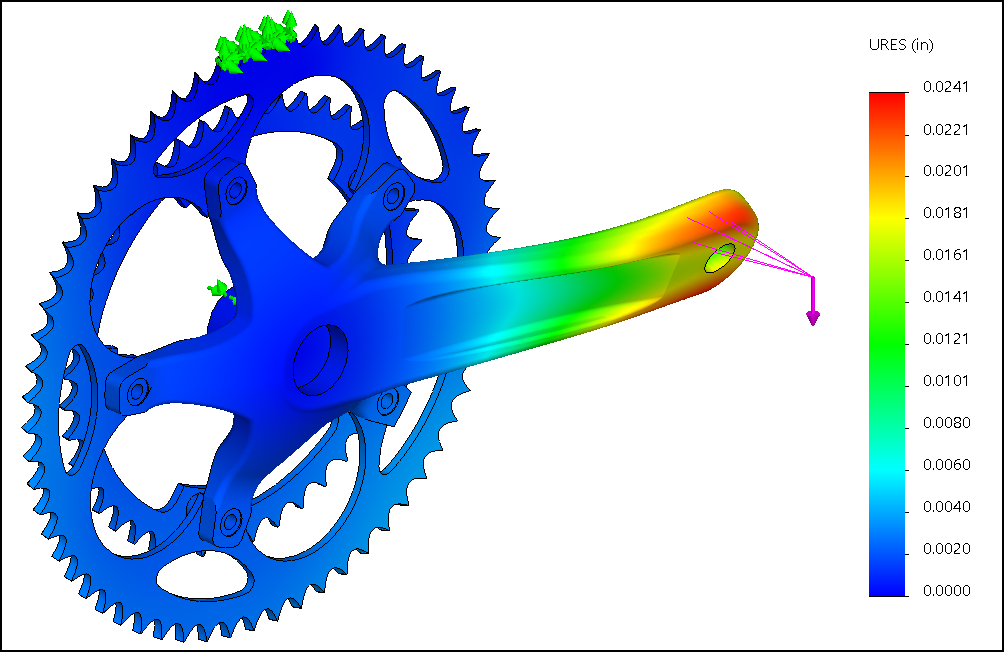

Although the climb up Highwood Pass felt difficult due to the altitude, the toughest part of our ride was the South East stretch to Longview, which is a small town in Alberta best known for not only its Heartland style Alberta cattle ranches, but more importantly its famous beef jerky. Half way up Highwood Pass I started to feel a pain from my right hip that radiated down to the top of my foot. I knew something in my hip was tight but pushed through, hoping that whatever had a death grip on my IT band would loosen itself up. It wasn’t until we hit the cross winds to Longview that my right leg began to really bother me. It almost felt like I had a dead leg. I was running a 4iiii PRECISION Pro Powermeter for our ride and saw my balance go from my typical 52/48 earlier in the ride to 65/35 meaning that my right leg was only doing 35% of the work, about the same amount of work that Bailey does during booth tear down at whatever cycling festival we are working at that weekend. My right leg did the equivalent of “I’ll go get the car. Left leg, can you pack up the 4iiii tent”?

A steady increase in heart rate once we hit the 2,000m mark.

A steady increase in heart rate once we hit the 2,000m mark.As we battled the crosswinds towards Longview, Scott was keeping a steady tempo and was definitely the strongest rider on the day. Scott, who joined us for our ride has some serious long distance pedigree in his legs. Formerly a pro Ironman triathlete, the current course record holder for Sinister 7, and Black Spur Ultra, Scott has the ability to push power for hours on end. His “Just Keep Swimming” attitude of Dory from Finding Nemo also pairs with his forgetfulness of how badly we suffer every time it was his turn to lead in the rotation. At 5’8, Scott rides an aggressively set up Cervelo S5. Scott is the only person that I’ve ever ridden with who gives off what seems like a negative draft. Every time I saw my power spike to the 270’s I’d pipe up reminding him of the 250w limit. He’d politely reply with a simple “I haven’t gone above 240w!”. Since then, we draw straws as to who has to ride behind Scott on the group rides as you are guaranteed the equivalent of a double pull when riding behind him.

After all of us were worn down and tired of being thrown around in the cross wind, we arrived in Longview exhausted, in need of a coke and a piece of salty beef jerky. I chased down two Tylenol’s with the remainder of my lukewarm Gatorade to help with the pain in my right leg. At 230km in, we turned North and made our way along the foothills back into Calgary. When checking the weather earlier that morning I had seen a tornado watch was listed for South West Calgary and to be on alert in the afternoon. Looking West towards the Rocky Mountains in the distance, a dark cloud could be seen approaching in the distance which was accentuated by the bright green pastures and cattle grazing off in the distance. Asking Mike what kind of omen a Tornado represents, he responded “I’m pretty sure it just cancels out the owl”. With the wind now on our backs we made a quick stop in a small town Millerville to do another restock of food and Gatorade. At this point we were 260km in and we were all starting to fade. I reached into the back pocket of my salt stained jersey and pulled out a Maurten gel (which I purchased through my local bike shop’s customer financing program the evening before). With the consistency of a Jello shot and the flavor of icing sugar I sucked back the gel and felt the energy come back into my body.

Shooting back my emergency Maurten gel in Millerville while Scott is ready to Rock n’ Roll and get back onto the road. I’m pretty sure Mike is pondering whether to dip into the Redbull this stop or to hold off for our final stop in Bragg Creek.

Shooting back my emergency Maurten gel in Millerville while Scott is ready to Rock n’ Roll and get back onto the road. I’m pretty sure Mike is pondering whether to dip into the Redbull this stop or to hold off for our final stop in Bragg Creek.At 270km into our ride, Scott’s tire slowly began to leak. It was bound to happen to one of us, but we finally had our first (but notably the only) flat of the ride. Rolling into Bragg Creek we reached our final stop before home. With a Snickers bar and Sprite in hand, I sat with Mike and Bailey on the steps outside of the Shell station at the Bragg Creek intersection where we watched the Canadian flag blow in the wrong direction. Shattered, we knew that only 50km remained in what was already an unforgettable day on the road. Clipping back in the flag changed directions and it seemed like that good omen earlier in the day came true. Sailing back into Calgary we averaged 41km/hr until we hit our final climb. Cresting to the top of Springbank the skyline of downtown Calgary glistened in the distance and at that point I knew that we had made it. We rolled back into Calgary and parted ways with Bailey (who proved that it’s possible to ride over 300kms on only 6 hours a week of training), while Mike, Scott and I took the bike path back to our homes where we started our journey at 5:30am that same morning.

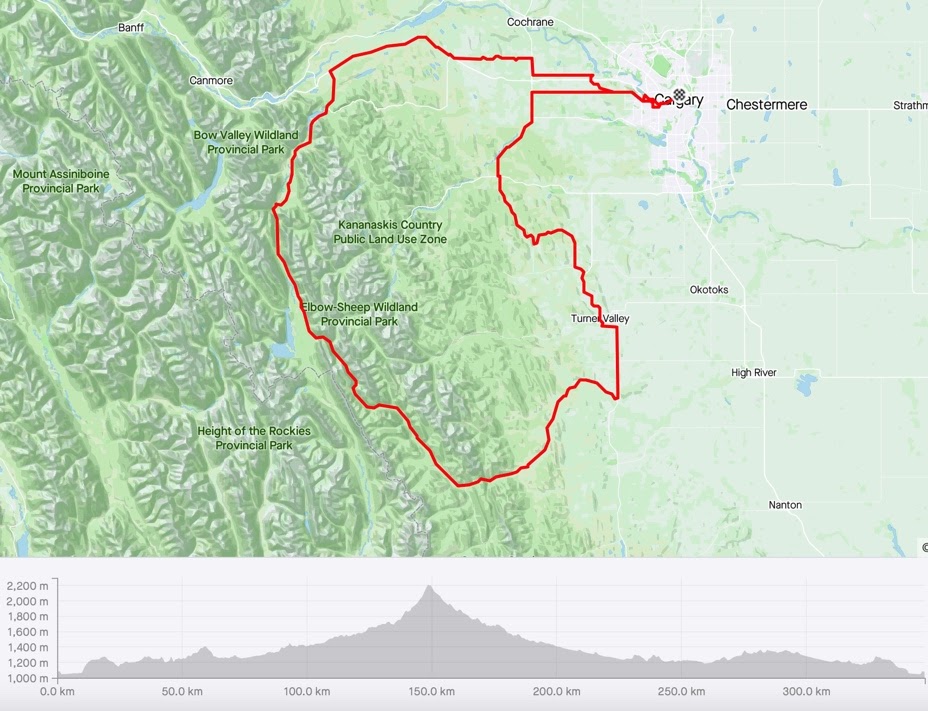

Complete map and elevation profile of our ride. That last little hill at 330km was harder than it looks…

Complete map and elevation profile of our ride. That last little hill at 330km was harder than it looks…An hour later, after showering and refueling with a whole pizza, we met at the local Brewery to share a pint and poutine to celebrate the epic journey that we all took on that day. Although struggling to stay awake I opened my phone to Google maps in search of our next adventure and I think I found one at 428km long. I turn to the boys, “Calgary to Jasper anyone”?

Distance: 347 km

Elevation: 3,608m

Ride Time: 10h56m

Avg Power/NP: 170/195

Avg Heart rate: 124 BPM

Avg Speed: 31.7 km/hr

Calories: 6,777

TSS: 385

Tornados: 0